Table of Figures:

Introduction

The fight against

hydraulic fracturing or fracking is similar in some respects to other

environmental struggles. In a typical

scenario, a powerful industry causes pollution and environmental degradation as

it subverts the political structure in order to defend its practices. Most of these fights are “David verses

Goliath” struggles. The distribution of

pollution sources and the strength and secretive nature of the industry all

make this a particularly tough fight. In

the case of fracking, the most powerful energy sector will not easily abandon the

possibility of profiting from more than 15 billion barrels of previously

untapped oil reserves in The Monterey Shale formation. California, though, will

see none of these resources since the oil recovered from the area is poor

quality crude that is below the state’s standards for use and refining.

Historical

alliances between the oil industry and the political establishment exempted the

practice from the CEQA (California Environment Quality Act) process. This exempt status hid environmental and

health effects in California. In recent

years, fracking methods advanced to horizontal wells that are much deeper than

previously drilled. These changes in

fracking have awakened awareness of its environmental impact. Gas fracking has caused water and air

pollution, as well as earthquakes, which highlight the practice’s impact. The practice of fracking is still shrouded in

mystery since the industry is not transparent about the specifics of their

techniques and the use of chemical compounds.

This mystery creates distrust among the public, which heightens when the

industry opposes regulation. The

Division of Oil Gas and Geothermal Resources (DOGGR) never required mandatory

registration of wells, extraction methods, water use or chemical disclosure up

to now. Therefore, communities are kept

in the dark about industry practices.

Environmental

activists are split about fracking regulation’s effectiveness on water resource

depletion, water contaminations and air pollution. Regulation, however, will not eliminate all

impacts of fracking nor would it help direct our economy towards a greener

energy future. In its pursuit of greater

profits, the oil industry stifles competition from green energy sources. The boom and bust oil and gas economy keeps

profit and control over resources in the hands of few wealthy multinational

corporations. The California economy and

environment would do far better promoting green energy sources such as wind and

solar.

AB32, the Global

Warming Solutions Act of 2006, directs the state to reduce its GHG (greenhouse

gas) outputs to 1990 levels by 2020; fracking would lead to the antithesis of

this goal. Although banning fracking is

an immense challenge, it is a powerful message to a defiant industry that

California is not buying its deception.

Oil industry jobs are risky and injury prone. Without a severance tax on oil, the industry

benefits at the public’s expense by exploiting scarce water resources and

polluting groundwater. In light of these

environmental and economic costs, fracking is not worth the benefits it

brings. Consequently, California would

do far better investing in the renewable energy sector.

The public could thwart

the numerous detriments of fracking by banning these operations

altogether. The ban would limit the

industry’s ability to extract the oil and eliminate California’s exposure to

this risky economic experiment.

Chapter 1 – Hydraulic Fracturing in California

What is Hydraulic Fracturing or Fracking?

Hydraulic

fracturing or fracking is a method of oil and natural gas production. In this process, oil and gas companies pump

large quantities of water mixed with sand and chemicals under high pressure

into underground wells to release the oil and gas bound within rock formations,

such as shale and coalbed.

The practice of

hydraulic fracturing started in 1947, when oil and gas producers used vertical

fracking techniques to increase production and prevent clogging (Suachy & Newell, 2011). In vertical fracking, a

shaft is drilled straight down. However,

the method has developed to an extended horizontal drilling that increases the

length and depth of previous practices (Suachy & Newell, 2011). The industry began this

new fracking practice of horizontal fracking in shale and coalbed formations by

fracking the same well several times (Suachy & Newell, 2011). This method allowed

companies to recover large quantities of oil and gas from wells that had

previously stopped producing.

Hydraulic Fracturing in California

Fracking began in

California in 1953 with vertical fracking; since then, tapped out oil wells use

fracking to restart production (Shearer, 2012). Today, horizontal fracking

opens up huge oil reserves in California.

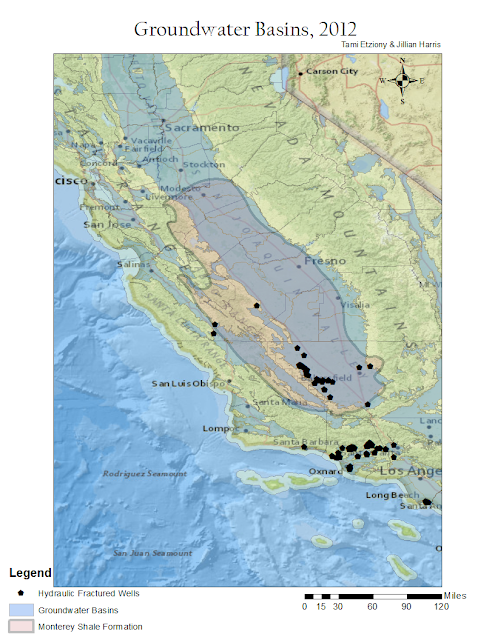

Industry sources say that over 600 wells used fracking in California in

2011 (Shearer, 2012). Most of these are oil

wells. The industry is reporting

fracking activity concentrations in Bakersfield, Los Angeles and areas north of

Sacramento (FracFocus, 2012).

Promising oil

reserves in the Monterey Shale Formation could only be accessed through

fracking methods. The reserves span the

distance south of Monterey and north of Santa Barbara and east to the San

Joaquin Valley. There are estimates of over

15 billion barrels of recoverable oil within the formation (Masterson, 2012). That translates to 630

billion gallons of gasoline. California

drivers use 16.5 billion gallons of gasoline per year (California Energy Commission, 2012). Hypothetically, the

reserves could possibly supply California with another 40 years of fuel. However, the crude oil from Southern

California is not processed or sold in California due to its poor quality, which

is equivalent to the crude extracted from the tar-sands in Canada. The industry exports this dirty crude to

places with lower environmental standards (Roberts, Grist.org, 2013).

Most fracked

wells in California are oil wells, which somewhat reduces the environmental

risks of this practice. Oil extraction

uses less water in comparison to gas production, so fracking in California does

not use as much water as in other places (Baker, 2012). Still the average water

use for fracking in California is about 164,000 gallons per well. That is an average use of a single golf

course watering per day (Baker, 2012). Furthermore, California

has limited water resources; the question is how many new golf courses

California’s water supply can support.

This issue is pivotal since we can expect many thousands of new fracked

wells in the coming years in a state that has diminishing ground water

reserves.

California is one

of seven states that oversee oil and gas explorations jointly with the U.S. Environmental

Protection Agency (EPA). The Division of Oil, Gas and Geothermal Resources

(DOGGR), the state government agency in charge of fracking regulation, has been

late in collecting information about the practice (Shearer, 2012). To date DOGGR, a

division of the Department of Conservation, has not issued regulation governing

hydraulic fracturing (Shearer, 2012). Federal regulators

informed DOGGR of deficiencies in its oversight in 2011 and required prompt

resolution (Shearer, 2012). That same year,

Governor Jerry Brown fired Derek Chernow, head of the Department of

Conservation and his deputy Elena Miller when they refused to relax regulations

on underground injections, a technique associated with fracking. Chernow and Miller argued that the proposed

lenient regulation standards would violate federal laws (Shearer, 2012). This case sheds light

on Governor Brown’s position on fracking.

Since state

regulators have not been effective, some local communities have gone ahead with

efforts to prevent environmental damage.

Fracking occurs in several cities in Los Angeles County, among them

Culver City, Los Angeles and Inglewood.

Oil fields dot the landscape, amidst a densely populated

metropolis. Communities are concerned

about the environmental harm that may result from this practice. Through litigation, citizen groups have reached

a settlement agreement that includes air quality monitoring and health

assessment (Baldwin City, 2012). This assessment

provision, however, is simply a Band-Aid solution to mounting concerns.

Chapter 2 – Pollution, Leaks and Water Resources

Contamination from Fracking

The

change in fracking practices to horizontal fracking increases concerns for

water and air quality as well as other health and environmental concerns

because the fracking activity happens below ground water tables. In Pennsylvania and New York, evidence show

that fracking for natural gas from the Marcellus and Utica shale formations has

resulted in contamination of ground water (Frosch, 2012) and farmlands (Fox, 2010).

Despite these concerns, fracking regulation is limited for several

reasons.

One

reason is the division of authority between the federal and state

governments. Another reason is the

narrow scope of U.S. EPA oversight authority under the Safe Drinking Water

Act. Since 2005, the notorious “Halliburton

loophole” exempts underground injections of chemicals from tight regulation

except for diesel fuel. The EPA has

acknowledged that there are health concerns related to this extraction method (EPA, 2011), and is currently conducting a study to

assess the impact of the practice on drinking water sources. Their study is due to be completed in 2015 (EPA, 2011).

The fracking

fluid is one of the main health concerns associated with fracking. A cocktail of chemicals, many of which are

highly toxic and carcinogenic, mixed with water and sand is utilized to break

up the rock formation to access the oil and gas bound within. The Congressional Committee on Energy and

Commerce minority staff report on the chemicals used in fracking listed

formaldehyde, naphthalene and benzene among the toxic chemicals components in

many fracking fluids.

The cocktail of

chemicals in the fracking fluid could leach out of the overflow pools to

contaminate local waterways and harm wildlife. Air pollution is another concern. Fracking releases ozone in the immediate area

as well as vapor from the volatile organic compounds (VOCs) in the overflow

pools. Finally, the practice could

potentially cause earthquakes, which is an understandable concern in California (Baldwin City, 2012).

Figure 1, Monterey Shale Formation and Ground Water (Deprtment of Water Resources, 2003) & (DOGGR, GIS

mapping - well sites, 2013)

The Lure of Financial Rewards vs. Land and Water Contamination

Complaints about hydraulic fracturing contamination in the

past several years have reverberated throughout gas production areas across the

country. Pennsylvania, New York, Wyoming

and Colorado are among the states that have experienced water and land contamination. In the 2010 movie “GasLand,” Josh Fox

traveled through these areas and collected fracking horror stories. Farmers are forced to purchase water to

replace their well water, which has been contaminated by fracking. Domesticated animals are exhibiting serious

health problems and wild animal carcasses are found by contaminated streams (Fox, 2010).

Extraction companies approach landowners with leasing

options that sound like winning the lottery, but leave the landowners with no

recourse when things go wrong. Lease

agreements for oil and gas extractions let these companies set up their

equipment and have road access to the well site. Truck traffic brings with it air pollution

and noise, and VOC’s vapor and spills expose farmland and streams to leaks and

contamination. Fox estimates the average

truck trips at 1150 per well for fracking purposes (Fox, 2010).

Unfortunately, the industry is neither careful nor caring,

as indicated by a comment that Mr. Tillerson CEO of Exxon, made to Forbes Magazine:

“The consequences of a misstep in a well”, he states,

“while large to the immediate people that live around that well, in the great

scheme of things are pretty small, and even to the immediate people around the

well, they could be mitigated…they are not life-threatening, they’re not

long-lasting, and they’re not new. They

are the same risks that our industry has been managing for more than 100 years

in the conventional development of oil and natural gas.” (Rogers D. ,

2013)

This statement is riddled with half-truths. Contaminated groundwater cannot be

mitigated. In case of spills into

farmland and riverbeds, costs are high and complete clean-up is

impossible. Health problems associated

with fracking have not been studied thus far, therefore, their consequences are

not known. The fracking practices have changed

in the past ten to fifteen years and are now more hazardous than before, as is

evident from the contamination and leaks on gas fracking sites.

In California, the practice was not scrutinized by CEQA

and therefore we just do not know the occurrence and extent of previous

impact. However, common knowledge of

infamous incidents such as those of Exxon-Valdez and BP Deepwater Horizon,

point to an industry that carelessly pollutes and drags the lawsuits on for

years with little accountability to the people and the environment.

Besides the fracking sites themselves, accidents and

spills occur on the miles of pipeline that crisscross the land. Between 2010 and 2012 there were 1,049

hazardous liquid pipeline accidents in the US (Dept. of Transportation, 2013). “Pervasive

organizational failure by a pipeline operator along with weak federal

regulations” was blamed for a particularly egregious spill in Yellowstone

National Park. The National

Transportation Safety Board Office of Public Affairs said there was a “culture of deviance” and systematic

flows in the operations of the pipeline (Knudson, 2012).

Water Issues: Contamination of Underground Sources

In East Coast states, numerous accounts report signs of

water contamination immediately after fracking.

The fracking initiates percolation of methane and other VOC’s into the

ground water table to such a degree that faucet water can be ignited and start

a fire. People in the affected area

complain of incessant headaches, neurological problems, brain lesions and

asthma among other health concerns (Fox, 2010).

The industry’s disregard of their practices’ impact is

evident. Tupper Hull, vice president of

strategic communications for the Western States Petroleum Association,

questions the purpose of disclosure of fracking fluid chemicals. He notes that disclosure after the fact is

just as valuable (one of DOGGR’s current recommendations). Yet the lack of proper and timely disclosure

limits testing before and after fracking activity, which would clearly indicate

the source of contamination. Moreover,

Hull contends that there are impervious layers of rock between ground water and

shale formations (Ratcliff, 2013). While this cannot be proven, evidence of

events of previous water contamination contradicts that assumption. In addition, California’s seismic activity

creates uneven geological layers therefore, by comparison to the East Coast;

fracking in California could cause even more damage by causing earthquakes (Roberts,

Grist.org, 2013).

Overflow Pools and Leaks

Fracking fluid overflow is contained in evaporation

ponds. Contaminated fracking fluid laced

with carcinogenic components can leak out of these ponds. Fracking drill sites vent fumes that pollute

the air to a level comparable to heavy city traffic. Vaporizing fountains promote speedy

evaporation, and disperse the chemicals over the surrounding area. Some of these ponds use plastic liners, but others

do not. Even when liners are used, they

can leak into streams and leach into ground water reservoirs. Without consistent federal regulations, the

community is at the mercy of the underfunded state regulators (Fox, 2010).

The consequences of the leaks are evident in the pistachio

and almond groves of Fred Starrh of Kern County. To compensate for water shortages in the 90’s

Starrh mixed ground water with his water allotment. His trees are planted adjacent to an industry

‘produced water’ or overflow pond. The

‘produced water’ seeped into his ground water and killed a large portion of his

trees. In 2009, he won $8.5 million in

damages from Aera Energy ponds, a joint venture of Exxon Mobile and Shell. The win is of little consolation since it

would cost hundreds of millions to flush out the contamination (Miller, 2011).

The aftermath of contamination is much more expensive and

complicated to fix than avoiding the contamination in the first place. The oil and gas industry fights even modest

regulation that could reduce contamination.

Common Cause reported that Exxon Mobil spent over $150 million lobbying

Washington to halt regulation in the past ten years (Common-Cause, 2011).

California’s Water is Too Precious for Fracking

Fracking in California requires less water, ‘only’

hundreds of thousands of gallons per well is used in comparison to millions of

gallons for gas fracking. This is still

too much for a water-strapped state.

In the 1980’s each barrel of oil extracted in California

used four and a half barrels of water in production. By 2008, the ratio went up to eight barrels

of water for one of oil (Miller, 2011). Fracking is dependent on substantial water

withdrawal. In the meantime, the

industry buys land above the Monterey Shale Formation for exploratory

wells. In the near future, we can expect

thousands more wells if this practice is allowed to proliferate.

Governor Jerry Brown proposes new water tunnels to supply

the water needs of Southern California (Blanchard, 2013).

The proposal permits the State and

Federal Water Contractors Association (SFWCA), founded by six water districts

to finance the construction of two tunnels that will divert water from Northern

California. These tunnels would

facilitate the sale of water from communities in Northern California to these

six water agencies (Bacher, 2013). In essence, this could place privatization

pressure on California’s water resources.

Environmental organizations perceive these plans as an additional

catalyst for fracking activity (Bacher, 2013). Fracking is not sustainable with the limited water

supply in our state.

The state Department of Energy; estimated water withdrawals

by oil companies in the 1980’s, in Kern County to be upwards of 12 billion

gallons a year (Miller, 2011). The oil production has cost the state heavily

in water resources utilized by an industry that pollutes at will and does not

pay taxes on the resource they extract.

The citizens of California deceive themselves; if they think that the state

watches over this industry. Oversight is

not adequately funded; therefore, inspections are insufficient (Miller, 2011).

Associated Earthquakes

Yet another concern that is crucial in California is

fracking-associated earthquakes.

Earthquakes have been reported in many fracking regions that did not

previously experience active faults (Behar, 2013). The National Research Council collected data

on human caused seismic activity due to energy technologies and concluded that

most fracking activities do not pose substantial risk for earthquakes. However, the secondary practice of discarding

overflow fracking fluid by injection wells does pose significant risks (Hitzman,

2012).

Yet another risk of this practice is the incidence of earthquakes

reported near fracking sites. In Texas,

a two-year study positively correlated concentration of small earthquakes

within 2 miles of fracked wells. For

unknown reasons, these small earthquakes were not reported by the National

Earthquake Information Center (Frohlich, 2012).

The Dallas airport, located in a region of substantial

fracking activity, experienced such earthquakes, in magnitude of 2 to 3.4 on

the Richter scale. The same area was

inundated with fracking overflow water (MacKinnon, 2012).

Without systematic data collection on fracking practices,

there is little information available on the scale of these overflow injections

but earthquakes occurred near many fracking sites. Southern and Central California is

interspersed with fault lines and fracking activity in particular injection

wells could trigger much larger earthquakes than in other fracking locations.

Figure 2, Map of Monterey Shale Formation and Earthquake Faults (USGS, 2010) & (DOGGR, GIS mapping -

well sites, 2013)

Chapter 3 – Why is fracking not worth the risk?

Economic Gains; At What Cost?

Depletion of water resources and earthquake damage are

part of oil explorations negative impacts.

These impacts have an economic value.

The industry saddles the communities around its operations with many

negative economic externalities.

Externalities are “unintended” consequences of an economic transaction

that fall on a third party (in this case the public) to pick up the tab. While the seller and buyer both benefit from

better prices, which do not include the added cost of the externalities, the

public incurs great loses from the transaction by covering and living with these

costs. Fracking fluid contaminations,

air pollution, job injuries and depleted water resources are all externalities of

the oil industry that suppress the California economy.

Oil and gas royalty and rental payments from BLM parcels

support local and state government and help develop parks. California benefited from pipeline right-of-way

rentals in 2011 to the tune of $1,150,461 (Bureau of Land Management, Rentals and Royalties FY2011, 2012). In addition, California received $88 million

in revenue from oil and gas production on BLM parcels (Dept. of the Interior, 2011). However, compared to the subsidies the

government gives the industry, it’s a wash and these revenues are not quite as appealing.

The wide spread myth that this industry acts as a good

citizen is sadly mistaken. We see time

and again that corporate negligence and mistakes burden the economy with

negative consequences. The tar-sands

crude oil spill in Arkansas in early April 2013, illustrates the inability of

the industry to protect the interests of the community in which it is

operating. A week earlier, a train

derailment in Western Minnesota spilled 300,000 gallons of crude (Song, 2013).

In Marshall, Michigan in 2010, one

million gallons of oil destroyed two miles of Talmadge Creek and almost 36

miles of the Kalamazoo River for several months; in addition, over 100 homes had

to be permanently relocated.

"People

don't realize how your life can change overnight," LaForge (A local home

owner) told an InsideClimate News reporter as they drove slowly past his empty

house in November 2011. "It has been devastating." (McGowen & Song, 2012)

These accidents represent operational costs to the

industry but their economic and environmental harm lasts long after the

industry recovers these costs.

Another economic loss is the missed opportunity of

investing in renewable energy. In

essence, California is supporting an industry that is not beneficial to the

same degree that an investment of the same magnitude in green energy would

be. The state invests in infrastructure,

education, reliable energy and water resources to support industry, which in

turn provides jobs and tax revenue. If

however, the state invests in an industry that pollutes, degrades our

environment and does not pay an equivalent level of taxes, than we are getting

the raw end of the deal.

The renewable energy sector creates three times the jobs that

the fossil fuel energy creates. The

quality of the jobs in green energy is higher employing twice the numbers of

credentialed jobs. These jobs pay better;

on average, green jobs pay $46,343 while other sectors are $38,616. Unfortunately, the federal government doles-out

subsidies to the fossil fuel industry at 75 times the amount that green energy

receives, a cumulative amount of $446.96 billion for fossil fuel vs. $5.93

billion for green energy (James, 2012). The oil industry subsidies are misguided,

since they produce far fewer benefits.

Since the federal government has moved very slowly on this

issue, many states, California among them, have established renewable

standards. These states are facing a

fierce backlash from the fossil fuel industry and conservative legislators (Plumer, 2013). In California, the struggle to establish

green energy standards was apparent in the fight over Proposition 23. The proposition would have suspended AB32,

the bill that creates greenhouse-gas reduction targets.

The oil and gas

industry pours money into Congress to sway representatives’ votes against

regulations. During a ten-year nationwide

campaign, this industry distributed $747 million effectively suppressing

fracking regulations (Browning & Clifford, 2011). We should expect strong opposition to

fracking regulations in California.

AB591 that proposed registration of wells, water use and disclosure of

the extraction method; died in the Appropriation Committee last year. AB972 recommended a ban on fracking practices

until DOGGR assessed its environmental harm.

This bill had an even shorter life span.

Tupper Hull, a trade organization vice president, said

that fracking is a gift to California and the result would be a “phenomenal success story” (Ratcliff, 2013). The oil however, is in the hands of private

industry. California has high standards

for transportation fuel. Due to the poor

quality of the oil produced in the state the oil extracted here will not be

refined or used in the state but exported elsewhere (Roberts, Grist.org, 2013). The only legacy left in California would be

pollution, depleted water resources and contamination.

AB 32, Climate Change; a Game Changer

Fracking for oil goes against established GHG standards in

California. AB32, the Global Warming

Solutions Act of 2006, requires California to reduce greenhouse gas (GHG)

emissions to 1990 levels by 2020. The California

Air Resources Board (CARB) is the lead agency authorized to implement the

law. The agency’s tools include

instituting a cap and trade system, increasing the renewable energy within the

state’s portfolio, promoting energy efficiency and establishing target

transportation emission reductions.

Fracking increases GHG emissions from operational procedures, gas leaks

and truck traffic.

Several studies looked at the GHG emissions from gas

fracking operations. Yet I found no

studies that compared GHG emissions from oil fracking operations to

conventional extraction. Natural gas

contains methane, which is a greenhouse gas with a different risk pattern than

carbon (CO2). Methane traps

twenty five times more heat than CO2. Methane is a key component of natural

gas. Many of the fracking practices for oil

extraction are comparable to those for gas extractions. For instance, overflow evaporation ponds vent

VOCs and cause air pollution. In

addition, the transportation of oil translates into many spills and accidents

that cause VOCs to escape and contribute to air pollution. Furthermore, the air pollution at fracking locations

increases due to heavy truck traffic. Collectively

these higher emissions do not align with AB32’s goal and would hamper

California’s efforts for GHG reduction.

Evidence points at escaped gas from fracking operations as

well as along the pipeline as the source of higher emissions. We can likewise expect some of these to be

true for oil production, since methane and other VOCs are present in the oil

reservoirs.

Hydraulic fracturing production of natural gas carries a

30% – 200% higher burden of GHG than conventional methods. A 2011, study accounts for the entire

life-cycle of each practice and calculates the reported methane emissions

conservatively. The reasons for the

increased emissions are fracking fluid flow-back that includes methane and the “drill-out”

stage, both of which happen at well completions. This study concluded, “The large GHG footprint of shale gas undercuts the logic of its use as

a bridging fuel over coming decades, if the goal is to reduce global warming”

(Howarth, Santoro, & Ingraffea, 2011).

Comparison between natural gas from fracking and coal GHG

emissions over their life-cycle reveals that shale gas (fracked gas) carries a

range of 0.87 up to 1.71 GHG burden compared to that of coal in the first

20-year span and 0.61 up to 0.88 burden in a 100-year span. Due to methane characteristics, that intensifies

GHG potency in the first 20 years but decreases in the long term, up to 100

years (Wang, Ryan, & Anthony, 2011).

A third study

looked at the GHG emissions of shale gas and compared flaring activity to

reduced emission “green” completions. Flaring

burns excess gas and emits hazardous pollution.

In an effort to consider cleaner options to flaring that creates

excessive pollution, the study compared other completion procedures. They assessed the fugitive emissions at 3.6%

of all natural gas production, which are the lowest estimates of all the

studies. The industry would not commit

to a maximum of 5% escaped gas, since it assumes the levels could be much

higher. They noted that “increased efforts must be made to reduce”

the fugitive emissions. Nevertheless, they

concluded that with better completion procedures, shale gas is comparable to

the rest of that sector (O'Sullivan & Paltsev, 2012).

Completion techniques refer to the

transition from fracking activity to capturing the extracted resource, whether

gas or oil, in pipelines.

Since the oil extracted in California is not of adequate

quality for state use, additional transportation (shipping) would increase its

life-cycle GHG emissions. Fracking

location emissions, pipeline leaks, transportation and the polluting nature of

heavy crude add up to a heavy GHG impact.

This increases GHG load, which contradicts the state’s goal of GHG

reduction.

California’s Oil Resources

The estimated 15+ billion barrels of oil are speculative

USGS assessments (Roberts,

Grist.org, 2013). Nevertheless, the reserves are expected to

supply oil for many years to come. In

calculating the economic benefits of the resource, global oil prices play a

large role. Gas prices plummeted in the

US due to fracking but remained high elsewhere (Kemper & Martin, 2013).

So far, that decline in price increased

demand on fracking for gas. Would

declining oil prices increase demand and thereby increase pressure on fracking

for oil? Reduced profits, on the other

hand, could spell an economic decline.

Canadian crude trades at discount prices these days and

historically has had high trading volatility.

“In

Canada, we have been shocked to see the opportunities for growth and potential

profits from unconventional energy sources evaporate before our eyes. Perhaps this story is worth telling in a

larger arena: what can we do to hedge the risks to companies and governments of

energy bubbles?” (Kemper & Martin, 2013)

Producing tar-sands oil is costly by comparison to

fracking, which may give preference to California crude and increase oil

company’s profits. Market volatility

however will stay a significant part of the equation for these dirty

fuels. Depending on such a volatile market

and energy sector that creates so many negative externalities is a bad bet for

California.

On the other hand, Deutsche Bank points out that solar

energy have reached the market price for electricity. Consequently, with or without subsidy,

renewable energy makes better economic sense (Kemper & Martin, 2013).

Renewable energy is more labor-intensive than the fossil

fuel industry and, therefore, creates more jobs per profit margin. If California wants to keep its economic

edge, we should invest heavily in solar and wind power. Our competition, Germany, is set to triple

its renewable sector jobs by 2030 from 2006 levels, which were already

comparatively high. In the US, 200,000

jobs belong to the green energy sector, and a third of that sector’s employment

is in China (World Watch

Institute, 2013). California will lose its economic prominence

if its investments follow dirty oil.

Recently, the Bureau of Land Management sold leases to oil

companies in the area around Bakersfield where fracking activity is ramping up

operation. In 2012, the BLM sold 23

thousand acres for an average of $56 an acre. While farmland prices rise, these lease prices

are dirt-cheap. Oil companies gobble up

these leases, seeing visions of oil profits.

The state, however, will not see much gain. Since DOGGR doesn’t keep full records of

fracking activities, the list of companies below includes only the ones who volunteered

the information.

Sale of public lands for oil production:

|

Total number of leases

|

28

|

|

Total acres under lease

|

22,917.35

|

|

Total revenues

|

$1,291,358.50

|

(Bureau of Land Management, Competitive Oil & Gas

Lease Sale, 2012)

Fracked wells operators and years of well activity:

Aera Energy LLC - 2011

DCOR, LLC - 2012

Mirada Petroleum Inc. – 2006, 2010

Renaissance Petroleum, LLC - 2010

Seneca Resources Corporation – 2011-2012

Vintage Production California LLC – 1997-2012

This list is not complete due to the voluntary nature of DOGGR’s

records (Conservation, 2012).

Chapter 4 – To Regulate or to Ban; That is the Question!

Until now, the

powerful oil industry has largely avoided fracking regulation. In states where regulations are in place,

they are inadequate and include loopholes.

By pouring money into the federal government, they averted strict

regulations and attempt to do the same in the states where they operate.

U.S. EPA Oversight and the “Halliburton Loophole”

Prior to 1997, fracking was not regulated under the Federal

Safe Drinking Water Act (SDWA). After a

lawsuit brought by Legal Environmental Assistance Foundation (LEAF), the 11th

Circuit Court constituted that hydraulic fracturing is “underground injection”

and therefore, fracking from coalbeds (which narrowed the scope of the

regulation) came under the jurisdiction of the federal SDWA (Rogers S. M.,

2009). The decision federalized fracking regulations. In response, the EPA fought the decision

asking the courts to clarify its mandate of supporting industry exploration

while conducting its oversight functions.

When the agency received the orders to use oversight but not impede the

industry, it initiated a “study” on fracking contamination though only from industry

and government sources. The US EPA

finally released a report on fracking in 2004, declaring that fracking does not

threaten underground drinking water (Rogers S. M., 2009).

The EPA Discounted Concerns over Fracking Practices.

Weston Wilson, an EPA whistleblower, argued that this sort

of scientific “packaging” occurred in the preparation of EPA’s fracing report,

urging that

“EPA

decisions were supported by a Peer Review Panel; however, five of the seven

members of this panel appear to have conflicts-of-interest and may benefit from

EPA’s decision not to conduct further investigation or impose regulatory

conditions.” (Wiseman, 2009)

In 2005, Congress amended the Energy Policy Act to exempt hydraulic

fracturing from regulation under the SDWA. The changed definition of “underground

injections” excluded regulating fracking fluid components. Nevertheless, the courts upheld the

regulation on diesel fuel when it is used in fracking fluid. Environmental organizations refer to the law

as the “Halliburton Loophole,” named for the company that developed the

technique (Rothberg, 2010). Vice President Dick Cheney, who once led the

company bearing the exemption’s name, championed the energy policy that

included the “Halliburton Loophole” which was a giveaway to the industry. The “Halliburton Loophole” deregulated the

extraction method and allowed the industry to keep the fracking fluid chemicals

secret (Rothberg, 2010).

Two recent attempts to regulate fracking on the federal

level did not make it out of committee.

The first, in 2010, was The American Power Act, introduced by John Kerry

and Joe Lieberman. It would have brought

fracking regulation under The Energy Planning and Community Act of 1986. The second, brought before the Senate in 2010

and again in 2011, would have reversed the “Halliburton Loophole” by mandating

fracking regulation under the Safe Drinking Water Act (SDWA) (Maule et al., 2013).

Common Cause reports that the gas industry gave $20

million to current members of Congress and upwards of $700 million in lobbying

campaigns to avoid oversight. The

industry targeted representatives who supported the “Halliburton Loophole” in

2005 (Common-Cause, 2011).

In March 2013, two new bills attempted to close the

loopholes enjoyed by the industry to date.

Rep. Jared Polis (D, CO) introduced the Breathe Act, HR1154, which would

repeal the exemption for oil and gas industry, allowing them to emit more air

pollution than other industries. The

Fresher Act, HR 1175, introduced by Rep. Matthew Cartwright (D, PA) would

eliminate the oil and gas exemption from permits required to prevent

storm-water runoff (Ollison, 2013).

With the current Republican predominance in Congress, the future

of these bills seems doomed. Federal

government inability to regulate fracking has left state and local governments

to fill in the regulatory gap. Communities

that experienced fracking activity are leery of the practice’s benefits. They can see the devastating aftermath

clearly and try to use zoning ordinances to curb the practice’s harmful

effects.

The Short Lived Benefits

The oil and gas industry claims that fracking leads to

additional jobs and economic growth but after review, these jobs are short

lived and the potential environmental harm long lasting and costly. A study by Cleveland State University

concluded that fracking areas of Ohio did not see more overall job growth by

comparison to other areas where no fracking occurs. This could point to a gain in fracking jobs

equal to a loss in farming and tourism jobs.

Even though fracking jobs may be better paid, they are not long lasting. Mothers Against Drilling in Our

Neighborhoods, an Ohio grassroots group, notes that the economic losses due to

pollution and leaks are not included in the equation. Such losses to fishing, parkland and organic

farming cannot be undone after fracking leaves an environmentally degraded

landscape (Apton, 2013).

Underneath an ad tempting people to own oil wells, an

Associated Press article in the Miami Herald discussed the legal battle between

states and local communities. When

cities and counties try to limit or ban fracking through zoning ordinances the

industry fights back using state regulatory power. State agencies are influenced heavily by

industry since they promote and approve extraction activity. The article describes the local argument against

pre-empting local zoning.

"This

case comes down to this," said Dryden Town Supervisor Mary Ann Sumner.

"Who should make the decision affecting the use of our land? The people

who live here, who can identify a particular bend in the road or hayfield or

sensitive wetland or bog? Do we have that choice or do we leave it to people in

corporate offices thousands of miles away who know nothing of our

lifestyle?" (Esch, 2013)

Many towns are concerned about contamination of ground

water due to fracking. State regulators’

function is to encourage the full use of natural resources. Consequently, they discourage waste in the mining

and harvesting of raw materials. Through

this capacity, the regulators are closely linked to industry. Local residents feel the environmental impact

of fracking directly and have less faith in industry practices.

In California DOGGR has opened the process to local

communities by holding meetings in affected areas. The agency opened the process as part of its

proposed regulation, announced December 2012.

With any luck, the process will encourage stronger regulations at the

state level.

Other States’ Regulations

Regulations of fracking vary from state to state. The division of authority between federal,

states and local governments defines the fracking regulations saga. Several states are currently in the midst of

an authority battle over fracking regulation.

ALEC, the American Legislative Council, a pro-industry legal think tank,

produced bills that strip local governments of their planning and zoning

authority while limiting federal oversight of industry practices in order to

keep disclosure loopholes (Currier, 2012).

State legislators have proven friendly to the industry by

passing bills such as Pennsylvania Act 13, Ohio HB 278, Idaho HB 464 and

Colorado SB 88 (Horn, 2012). Act 13 imposes hefty fees for unconventional

drilling practices such as fracking (Rubinkam, 2012), but restricts local

planning and zoning laws in exchange for impact fees and limited disclosure (Ross, 2012). Act 13 also grants the industry the power to

obtain property through eminent domain.

In retaliatory action, the state withheld local impact funds from local

governments that attempted to limit fracking near schools, parks and

residential areas. (Rosenfeld, 2012).

Alabama regulates fracking from coalbeds through a program

approved by the US EPA in 2000. The

regulation established a registration program with administrative costs passed

to well owners at $175 per well (Rogers S. M., 2009). The registration does include an exemption

from disclosure of the proprietor’s secret fracking fluid components.

In an effort to regulate fracking fluid components, a bill

similar to California’s AB591 passed in Wyoming in 2010 (Kusnetz,

2010). Wyoming established the regulation to prevent

US EPA from regulating wells under federal standards. This law, however, includes a loophole that

allows extraction companies to exempt certain chemicals they consider industry

secrets (Fugleberg, 2011). Although the provision was not expected to be

used much, in the first year, companies used the exemption on 146 occasions (Kusnetz,

2010). This overuse of regulatory exemption indicates

that fracking fluid components would evoke a strong response from the community

that carries the risk of contamination.

Three other states - Arkansas, Pennsylvania and Tennessee

- require limited disclosure of fracking chemical use, but the disclosed

information is not available to the public (The Wilderness Society, 2011). The Wilderness Society stated in their survey

of state regulations that “almost all

states where drilling occurs have not taken steps to ensure that the

public…know what is being injected underground during natural gas drilling.” (The

Wilderness Society, 2011)

New York State took a preemptive stance by placing a

moratorium on fracking until the EPA releases its study of the practice. Formerly a two-year ban was extended by the

Assembly due to delays in the EPA study, now expected in 2015. Now the moratorium waits for Senate approval (Energy-Solutions-Forum, 2013).

In the past couple of months, Illinois put together a

coalition of industry and environmental groups in an attempt to create strict

fracking regulations. The industry pulled

out, however; due to fresh water-well unions’ demands that a certified water

contractor be on-site until the industry educate their employees and comply

with the regulation fully. The state has

two moratorium bills that have not made it out of committee. Both require studying fracking impacts for

two years prior to establishing regulations (Wernau, 2013).

Regulations in California

In California, the fight has just begun. The Federal Bureau of Land Management (BLM)

started selling land parcels to oil industry in several counties. Unfortunately, these land deals are under

federal regulation. By reneging on their

chemical disclosure requirements and air quality compliance standards, the Obama

administration catered to industry demand (Broder, 2012).

DOGGR, under public scrutiny, initiated a study of the

practice and announced that draft regulations would be published in January 2013,

with adoption of final regulation by August 2013 (Hagstrom,

2012). In December 2012, a preliminary proposal by

DOGGR received a tepid reception from environmental groups. The Sierra Club and other environmental

organizations sued DOGGR in October 2012, demanding that oil and gas

exploration, particularly fracking, should trigger an Environmental Impact

Report (EIR) process under the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA) (Hagstrom,

2012). Currently this activity has enjoyed

categorical exemption as a ‘minor alteration’ to land (Hagstrom,

2012).

In February 2011, California Assembly Members Wieckowski

and Butler introduced fracking regulations AB591 and AB972 respectively. The first would require registration of all

oil and gas production wells while the second bill set up a moratorium on fracking

until the state studied this extraction method and its environmental

risks. Both bills moved quickly through

the committee process in the 2011-12 legislative session. Although the bills died before reaching the

Appropriation Committee due to industry pressure, they may be the basis for

future legislative action (Mills, 2011).

In December 2012, The Sierra Club and The Center for

Biological Diversity filed a lawsuit that requires an EIR for fracking activity,

which DOGGR currently exempts.

In the meantime, oil companies are purchasing Bureau of

Land Management parcels. To date, BLM

sold thousands of acres in Monterey, Kern, Fresno and San Bonito Counties (BLM, 2012). These leases are subject to NEPA (National

Environmental Policy Act) under federal law.

However, since a prolonged contract agreement could stifle industry

progress, a tiered process evaluates EA (environmental assessment) at each step

of the land development. These EAs list

possible environmental degradation but they leave the critical oversight to

local air and water boards. (Bureau of Land Management, May 8

2013 Oil & Gas Lease Sale Environmental Assessment, 2012)

Pending Bills 2013

In the current legislative session, there are several

bills addressing fracking concerns. These

new proposed fracking regulations are:

AB 7, introduced by Assembly Member Bob Wieckowski would

require standardized rules for construction, public notification and chemical

disclosure adopted by January 1st 2014 (Ollison,

2013).

AB 288, introduced by Assembly Member Marc Levine,

requires DOGGR to establish a fracking specific permit process and authorizes

DOGGR to collect a fee for regulation costs.

Three Assembly Members from fracking affected areas,

Richard Bloom, Holly Mitchell and Adrin Nazarian introduced AB 1301, AB 1323

and AB 649. These bills would place a

moratorium on fracking until a study of its impacts would establish the

conditions permitting this practice (Nowicki, 2013).

AB 669, introduced by Assembly Member Mark Stone, proposes

that a regional water quality board approve a plan for disposal of wastewater

prior to fracking activity (Ollison, 2013).

AB 982, introduced by Assembly Member Das Williams, would

establish a ground-water monitoring plan administered by DOGGR and the Regional

Water Quality Control Board for every well employing fracing activity. These plans must include a description of

ground water in the particular location, disclose fracking fluid components and

establish oversight of fracking activity to detect contamination.

SB 4, introduced by State Senator Fran Pavley, which at

first required chemical and water use disclosure, was amended to include a moratorium

prior to an impact study as well as a specific registration for fracking

activity. The bill requires the Natural

Resources Agency to complete the study by 2015; however, if not completed in

time the bill extends the moratorium until the study’s completion (Seifried,

2013).

SB 241, introduced by Senator Noreen Evans, would impose a

severance tax on oil production (Ollison, 2013).

SB 395, introduced by Senator Hannah-Beth Jackson, would

regulate fracking “produced water” (overflow).

The bill defines “produced water” as a hazardous waste and authorizes

the Department of Toxic Substances Control (DTSC) to regulate fracking fluid

overflow (Seifried, 2013).

In such a jumble of proposals, it is hard to imagine a

coherent and comprehensive legislation emerging. The multitude of approaches to this problem,

illustrate the complexity of this issue and the numerous problems resulting

from fracking. Regulations would help

curb some environmental damage but it will not significantly cut water use or

the problems resulting from produced water.

The Precautionary Principle

The precautionary principle is a legal approach that

dictates an assessment of the hazards related to a product or a practice and

applies preventive measures before approving industrial production. According to this principle, the burden of

proof for harm to people and/or the environment lies with the industry. This approach attempts to mitigate possible

risk prior to the harm done since it’s difficult to “clean up the mess” once

it’s done. The European Union had made

this principle into a statutory requirement.

The California bills proposing to study fracking before

continuing the practice are an example of the precautionary principle in

practice. New York State effectively

acted within the spirit of the precautionary principle by continuing the

fracking moratorium until the EPA publishes its study.

Legal implications of the precautionary principle would

translate risks to a weighted burden of proof.

Anticipating the magnitude and probability of harm would shift the

burden of proof to the industry. The

industry must prove that their practices are safe.

In the US, the principle could also compliment the

anticipatory nuisance doctrine. Environmental

damage is legally difficult to litigate since the claimant must show

causation. However, the nuisance

doctrine can help neighbors of fracking activity receive compensation for harm

and loss to property value. Thereby, achieving

legal success prior to regulation expected when the EPA study is released in

2015 (Lees, 2012).

Chapter 5 – Political Feasibility for a Ban

The Current Political Landscape

For the past three years, environmental groups have ramped

up a campaign against “fracking as usual” in California. The Center for Biological Diversity and Food

and Water Watch and Credo gather signatures for banning the practice, while

other groups inform their members and push for regulations.

The groups are fragmented in their approach but unified in

their aim, to protect California from environmental harm. The Environmental Defense Center is calling

for a moratorium on fracking until adequate regulation is in place. The League of Women Voters also supports

tighter regulations. DOGGRs proposed

regulation lacks full disclosure of fracking chemicals and provides little time

for public notification (Ratcliff, 2013).

Santa Barbara County Supervisor Doreen Farr said, “We

heard from everybody, city dwellers, county dwellers, farmers, ranchers,

vintners, water districts, in addition to those environmental groups that

always follow oil issues very closely.”

The board passed amplified requirements for land use code for fracking. People are concerned about water

contamination, water scarcity and lack of disclosure, all of which diminish

public confidence in the industry (Rivers, 2013).

Creating the Campaign’s Strategy and Message

Environmental organizations have won and lost campaigns based

on the strength and inclusivity of their message. Introducing images and concepts from other

spheres of life broadens the support and increases the impact of a campaign. When John Muir created the image of the “cathedral

of redwoods” invoking a religious experience, it resonated with the

public. When Lois Gibbs struggled to

relocate the Love Canal residents, her campaign gained authenticity and authority

due to her own child’s health issues.

She was protecting her son, which is a powerful image.

The campaign to ban fracking needs to include a broad

spectrum of people without losing the impact of the message. Environmentalists must remember that farmers

are an integral icon in American culture and they cannot afford to isolate or alienate

California farmers. Prop 37 was defeated

in the past election cycle, in part, by the image of the concerned farmer that

the opposition to GMO labeling presented correctly, or not, but certainly effectively

to the California voters. Farmers have

been at odds with environmental groups over water issues for decades. Environmentalists must create new alliances

in order to include the farmers of the San Joaquin Valley in this struggle. Farmland water is at risk; that message has

to originate and be articulated by the farming community, not the environmental

movement. The Valley’s community has

more legitimacy in their complaints about water contamination, since the

environmental movement is not associated with that location. The farmers are fighting to protect their

land and that message is compelling and vital to this campaign.

Pointing out pollution levels and ground water

contamination is only the beginning. The

real conflict is the economic one.

Environmental groups must expand their arguments to include green job

creation and the narrow scope of economic benefits that fossil fuels provide.

A Proposition to Ban Fracking

As indicated by the slough of regulation bills this year,

fracking poses a complex problem. A proposition

for a ban on fracking could provide an alternative legislative avenue. Analyzing previous proposition’s success and

failure could shed light on the outcome of such an effort. A suitable comparative model is the voting

record of Prop 23. Prop 23 can provide

the analytic basis for a fracking ban campaign because its relation to the oil

industry.

Proposition 23 was drafted by the oil and gas industry in

an effort to halt AB 32’s GHG reduction measures until unemployment drops below

a certain level for a whole year. This

attempt to derail GHG controls is the mainstay of an industry bent on profiting

from a highly polluting resource.

Fortunately, the proposition failed and AB 32 is implementing systems to

decrease GHG.

The fall 2010 election demographics would present a

comparable election circumstance with fall 2014, being mid-cycle presidential

and gubernatorial election.

Understanding the demographic make-up would allow a reasonable

comparative model. In 2010, the high

turnout of almost 60 percent included a higher percent of Latino vote than ever

before (McGreevy, 2010).

California’s voters rejected Prop 23 by a wide margin, 38

for and 62 against. Among the different

ethnic groups emerges a picture that contradicts common assumption about who is

an environmentalist. Incidentally, the

segments of the state population that presented the strongest opposition to the

proposition were people of color 73 percent compared to 57 percent of whites; not

your white, middle class, Birkenstock wearing Sierra Club member. Community grass-roots organizations such as

the Ella Baker Center for Human Rights and the Asian Pacific Environmental

Network (APEN) along with many others connected with the diverse ethnic and

social mix that makes up the California population (Hertsgaard,

2012).

A 2010 Los

Angeles Times/USC poll found that 50 percent of Latinos and 46

percent of Asian-Americans “personally worry a great deal about global

warming,” compared with 27 percent of whites. Likewise, significantly more Latinos and

blacks see air pollution as a serious health threat, according to the last

three years of annual statewide surveys by the nonpartisan Public Policy

Institute of California. (Hertsgaard, 2012) Therefore, a “get out the vote effort”, media

campaigns and organizational out-reach must cover a wide spectrum of

communities and create inclusive messages.

Conclusion

“Fracking

is an environmental nightmare,” said Dan Jacobson, legislative director of

Environment California. “It pollutes our

water, contaminates our air, destroys our beautiful places and keeps us

addicted to fossil fuels. We need to ban

fracking now.” (Nowicki, 2013)

Although fracking

has been in California for over 50 years, the Monterey Shale Formation reserves

would increase the fracking activity to levels not seen before in the

area. Since the industry has enjoyed exemption

from environmental review, it is difficult to assess the pollution and environmental

degradation it has caused. Nevertheless,

there are enough incidents to indicate that the industry is not exceedingly concerned

with their environmental impacts.

Furthermore, their efforts to suppress regulation diminish the public

trust.

The oil industry’s boom and bust economy diverts resources

from the more productive renewable energy.

The goals set by AB32 are not consistent with fracking operations since extracting

heavy crude conflicts with California’s GHG standards. In addition, investing in green energy would

boost California’s competitive edge.

Finally, fracking uses scarce water resources that

California cannot adequately provide.

This practice diminishes the state agricultural capacity, with very

little to show for the high water demand.

For such small economic gains at such large environmental costs, a ban

on fracking would free water resources and funds for a sustainable economic

future.

Recognition

I would like to recognize and thank Jillian Harris for her

GIS map skills, of these distinct and insightful images of the Monterey Shale

Formation.

Works Cited

Apton, J. (2013, March 22). Ohio fracking boom has

not brought jobs. Retrieved March 27, 2013, from Grist.org:

http://grist.org/news/ohio-fracking-boom-has-not-brought-jobs/?utm

source=facebook&utm medium=updates&utm campaign=socialflow

Around the Capitol. (2011, February 16th). Assembly

Bill #591. Retrieved October 2012, from aroundthecapitol.org.

Bacher, D. (2013, March 15). Peripheral tunnel

water will go to agribusiness and oil companies. Retrieved April 20, 2013,

from DailyKos.com:

http://www.dailykos.com/story/2013/03/15/1194465/-Peripheral-tunnel-water-will-go-to-agribusiness-and-oil-companies

Baker, D. R. (2012, September). Fracking in

California takes less water.

Baldwin City, O. W. (2012, August). Fracking in Culver

City.

Ballot Pedia, b. (2013, February 27). California

Proposition 23, the Suspension of AB 32 (2010). Retrieved April 25, 2013,

from ballotpedia.org:

http://ballotpedia.org/wiki/index.php/California_Proposition_23,_the_Suspension_of_AB_32_(2010)

Ballot Pedia, b. (2013, February 18). California

Proposition 37, Mandatory Labeling of Genetically Engineered Food (2012).

Retrieved April 25, 2013, from Ballot Pedia.org:

http://ballotpedia.org/wiki/index.php/California_Proposition_37,_Mandatory_Labeling_of_Genetically_Engineered_Food_(2012)

Behar, M. (2013, March/April). Fracking's Latest

Scandal? Earthquake Swarms. Retrieved April 20, 2013, from

MotherJones.com:

http://www.motherjones.com/environment/2013/03/does-fracking-cause-earthquakes-wastewater-dewatering

Benchmark Communications, o. a. (n.d.). Advertising

on the Internet. Retrieved April 25, 2013, from BMCommunications.com:

http://www.bmcommunications.com/int_ad.htm

Blanchard, J. (2013, March 17). Delta twin-pipe

plan moves ahead. Retrieved March 29, 2013, from SFgate.com:

http://www.sfgate.com/opinion/editorials/article/Delta-twin-pipe-plan-moves-ahead-4359512.php

BLM. (2012, December 13). BLM Oil and Gas Lease

Auction Brings in over $104 Thousand. Retrieved March 27, 2013, from

www.blm.gov/ca: http://www.blm.gov/ca/st/en/info/newsroom/2012/december/CC1220_leasesaleresults.html

Broder, J. M. (2012, May 4). New Proposal on

Fracking Gives Ground to Industry. Retrieved April 4, 2013, from New York

Times.com: http://www.nytimes.com/2012/05/05/us/new-fracking-rule-is-issued-by-obama-administration.html?_r=0

Browning & Clifford, J. a. (2011, November 10). Fracking

for Support: Natural gas industry pumps cash into Congress. Retrieved

March 27, 2013, from Common Cause: http://www.commoncause.org/atf/cf/%7BFB3C17E2-CDD1-4DF6-92BE-BD4429893665%7D/Ohio--Deep%20Drilling%20Deep%20Pockets%20Nov%202011%202.pdf

Bureau of Land Management, B. (2012, December 20). Competitive

Oil & Gas Lease Sale. Retrieved April 13, 2013, from Bureau of Land

Management: http://www.blm.gov/ca/st/en/prog/energy/og/instructions/leasesale/2012.html

Bureau of Land Management, B. (2012). May 8 2013

Oil & Gas Lease Sale Environmental Assessment. Retrieved April 6,

2013, from Bureau of Land Management:

http://www.blm.gov/pgdata/etc/medialib/blm/ca/pdf/bakersfield/NEPA/2012.Par.64767.File.dat/DOI-BLM-CA-C060-2012-0247-FONSI.pdf

Bureau of Land Management, B. (2012, June 29). Oil

and Gas Operations. Retrieved February 24, 2013, from www.blm.gov:

http://www.blm.gov/ca/st/en/fo/bakersfield/Programs/Minerals/bkfo_minerals.html

Bureau of Land Management, B. (2012). Rentals and

Royalties FY2011. Retrieved April 14, 2013, from Bureau of Land

Management: http://www.blm.gov/public_land_statistics/pls11/pls3-27_11.pdf

Bureau of Land Management, B. (2013, 02 22). Competitive

Oil & Gas Lease Sales. Retrieved February 24, 2013, from www.blm.gov:

http://www.blm.gov/ca/st/en/prog/energy/og/instructions/leasesale/2013.html

California Energy Commission. (2012, October). Consumer

Energy Center.

Common-Cause. (2011, November 10). Fracking for

support: Natural gas industry pumps cash into Congress. Retrieved March

28, 2013, from www.commoncause.:

http://www.commoncause.org/site/apps/nlnet/content2.aspx?c=dkLNK1MQIwG&b=4773613&ct=11492861

Conservation, C. D. (2012, October 17). GIS maping

of wells in California. Retrieved February 12, 2013, from

www.conservation.ca.gov:

http://www.conservation.ca.gov/dog/maps/Pages/GISMapping2.aspx

Currier, C. (2012, April 24). ALEC and ExxonMobil

Push Loopholes in Fracking Chemical Disclosure Rules. Retrieved April 4,

2013, from propublica.org:

http://www.propublica.org/article/alec-and-exxonmobil-push-loopholes-in-fracking-chemical-disclosure-rules

Deprtment of Water Resources, D. (2003, June 27). California's

Groundwater: Bulletin 118. Retrieved April 18, 2013, from

www.water.ca.gov:

http://www.water.ca.gov/groundwater/bulletin118/gwbasin_maps_descriptions.cfm

Dept. of the Interior, D. (2011, November 7). Interior

Distributes $11.2 Billion in Energy Revenues to State, Tribe and Federal Governments.

Retrieved April 14, 2013, from U.S. Dept. of Interior:

http://www.onrr.gov/about/pdfdocs/11BillionMineralsrevenuesRevised_v2.pdf

Dept. of Transportation, P. &. (2013, March 29). National

Hazardous Liquid Onshore: All Reported Incidents Summary Statistics: 1993-2012.

Retrieved April 10, 2013, from Pipeline & Hazardous Materials Safety

Administration:

http://primis.phmsa.dot.gov/comm/reports/safety/AllPSI.html?nocache=1770#_liquidon

DOGGR. (2011). Producing Wells and Production of

Oil, Gas and Water by County - 2011. Retrieved March 26, 2013, from

www.consrv.ca.gov:

ftp://ftp.consrv.ca.gov/pub/oil/temp/NEWS/Producing_Wells_OilGasWater_11.pdf

DOGGR. (2013, March 6). GIS mapping - well sites.

Retrieved April 4, 2013, from Department of Conservation:

http://www.conservation.ca.gov/dog/maps/Pages/GISMapping2.aspx

Energy-Solutions-Forum. (2013, March 14). NY

Assembly Votes to Extend Fracking Moratorium Until 2015. Retrieved April

6, 2013, from AOLEnergy.com: http://energy.aol.com/2013/03/14/ny-assembly-extends-fracking-moratorium-until-2015/

EPA, U. (2011). Hydraulic Fracturing.

Esch, M. (2013, March 13). Town bans on fracking

to appeals court. Retrieved March 21, 2013, from Miami Herald:

http://www.miamiherald.com/2013/03/21/3297895/ny-appeals-court-to-consider-local.html

Fox, J. (Director). (2010). GasLand [Motion

Picture].

FracFocus. (2012, September). FracFocus.org.

Frohlich, C. (2012). Two-year survey comparing

earthquake activity and injection-well locations in the Barnett Shale, Texas.

Frosch, D. (2012, June 2nd). In Land of Gas Drilling,

Battle for Water That Doesn't Reek or Fizz. The New York Times.

Fugleberg, J. (2011, August). Wyoming regulators keep

146 fracking chemicals secret. Star-Tribune @ Trib.com.

Hagstrom, E. L. (2012, October 25th). Using CEQA to

regulate hydraulic fracturing.

Hansen, E. D. (2012). Understanding the Life Cycle

and Regional Impacts of Hydraulic Fracturing in the Marcellus Shale Basin.

Retrieved November 2012, from Robert & Patricia Switzer Foundation: http://switzernetwork.org/grant-programs/awards/understanding-life-cycle-and-regional-impacts-hydraulic-fracturing-marcellus-s

Heathman, E. (2012, August 13). Fracking – an

emerging economy often misunderstood. Retrieved November 2012, from

RuidosoFreePress.com:

http://www.ruidosofreepress.com/view/full_story/19794177/article-Fracking-%E2%80%93-an-emerging-economy-often-misunderstood

Hertsgaard, M. (2012, December 5). Latinos Are

Ready to Fight Climate Change - Are Green Groups Ready for Them? Retrieved

April 15, 2013, from The Nation.com:

http://www.thenation.com/article/171617/latinos-are-ready-fight-climate-change-are-green-groups-ready-them#

Hitzman, M. W. (2012). Induced Seismicity Potential

and Energy Technologies.

Horn, S. (2012, October). Exposed: Pennsylvania

Act 13 Overturned by Supreme Court, Originally an ALEC Model Bill.

Retrieved from CommonDreams.org.

Howarth, R. W., Santoro, R., & Ingraffea, A.

(2011, March 13). Methane and the greenhouse-gas footprint of natural gas

from shale formations. Retrieved December 13, 2012, from Springerlink.com.

James, A. (2012, March 12). Fact Sheet: 6 Things

You Should Know About The Value Of Renewable Energy. Retrieved April 4,

2013, from ThinkProgress.org:

http://thinkprogress.org/climate/2012/03/28/453122/fact-sheet-6-things-you-should-know-about-the-value-of-renewable-energy/

Kemper & Martin, A. a. (2013, March 21). Volatile

fossil fuel prices make renewable energy more attractive. Retrieved April

1, 2013, from The Gardian: http://www.guardian.co.uk/sustainable-business/blog/fossil-fuel-prices-renewable-energy-attractive

Knudson, P. (2012, July 10). Pipeline Rupture and

Oil Spill Accident Caused by Organizational Failure and Week Regulations.

Retrieved April 9, 2013, from NTSB Press Release: http://www.ntsb.gov/news/2012/120710.html

Kusnetz, N. (2010, September). Wyoming Fracking

Rules Would Disclose Drilling Chemicals. Retrieved from ProPublica.

Lees, Z. (2012). Anticipated Harm, Precautionary

Regulation And Hydraulic Fracturing. Vermont Journal of Environmental Law,

13, 575-611.

MacKinnon, E. (2012, October 2). Unusual Dallas

Earthquakes Likely Linked to Fracking, Expert Says. Retrieved March 7,

2013, from Live Science: http://www.livescience.com/23638-unusual-dallas-earthquakes-linked-to-fracking-expert-says.html?utm_source=feedburner&utm_medium=feed&utm_campaign=Feed%3A+Livesciencecom+%28LiveScience.com+Science+Headline+Feed%29

Masterson, K. (2012, September). California: The

Next Fracking Frontier? Retrieved from CapRadio.org.

Maule et al., A. L. (2013). Disclosure of Hydraulic

Fracturing Fluid Chemical Additives: Analysis of Regulations. NEW

SOLUTIONS: A Journal of Environmental and Occupational Health Policy,

167-187.

McGowen & Song, E. a. (2012, June 26). The

Dilbit Disaster: Inside The Biggest Oil Spill You've Never Heard Of, Part 1.

Retrieved April 5, 2013, from InsideClimateNews.org:

http://insideclimatenews.org/news/20120626/dilbit-diluted-bitumen-enbridge-kalamazoo-river-marshall-michigan-oil-spill-6b-pipeline-epa

McGreevy, P. (2010, December 11). California voter

turnout is highest since 1994 gubernatorial election. Retrieved April 25,

2013, from LA Times.com: http://articles.latimes.com/2010/dec/11/local/la-me-vote-tally-20101211

Miller, J. (2011, January/February). The

Colonization of Kern County. Retrieved March 28, 2013, from Orion

Magazine: http://www.orionmagazine.org/index.php/articles/article/6047/

Mills, M. (2011, September 12th). Proposed California

Legislation to Regulate Hydraulic Fracturing Stalls in State Senate with a New

Hydraulic Bill Poised for Introduction.

Nowicki, B. (2013, March 22). Three New Bills Seek

to Halt California Fracking . Retrieved April 6, 2013, from

BiologicalDiversity.org: http://www.biologicaldiversity.org/news/press_releases/2013/fracking-03-22-2013.html

Ollison, B. (2013, March 15). HBW Resources:

Ollison Fracking Report. Retrieved April 6, 2013, from mzehrhbw:

http://mzehrhbw.wordpress.com/2013/03/15/hbw-resources-ollison-fracking-report/

O'Sullivan, F., & Paltsev, S. (2012). Shale gas

production: potential verses actual greenhouse gas emissions. Environmental

Research Letters (7), 044030.

Plumer, B. (2013, March 26). The biggest fight

over renewable energy is now in the states. Retrieved April 2, 2013, from

Governor's Wind Energy Coalition:

http://www.governorswindenergycoalition.org/?p=5253

Ratcliff, M. (2013, January 10). Draft fracking

regulations from state draw mixed reviews locally. Retrieved February 24,

2013, from Ojai Valley Blog: http://ovnblog.com/?p=7259

Rivers, K. (2013, February 14). Vanture County

Supervisor Steve Bennett testifies at fracking hearing in Sacramento.

Retrieved February 24, 2013, from Ojai Valley News Blog:

http://ovnblog.com/?p=7370

Roberts, D. (2013, March 18). Retrieved March 28,

2013, from Grist.org:

http://grist.org/climate-energy/top-10-reasons-why-fracking-for-dirty-oil-in-california-is-a-stupid-idea/

Roberts, D. (2013, March 18). Grist.org.

Retrieved March 29, 2013, from 10 reasons why fracking for dirty oil in

California is a stupid idea:

http://grist.org/climate-energy/top-10-reasons-why-fracking-for-dirty-oil-in-california-is-a-stupid-idea/

Rogers, D. (2013, January 22). ExxonMobil and the

Precautionary Principle: part 2. Retrieved March 27, 2013, from Energy

Policy Forum.org:

http://energypolicyforum.org/2013/01/17/exxonmobil-and-the-precautionary-principle/

Rogers, S. M. (2009). History of Litigation

Concerning Hydraulic Fracturing to Produce Coalbed Methane.

Rosenfeld, S. (2012, March). How an

Anti-democratic, Corporate-friendly Pennsylvania Law has Elevated the Battle

over Fracking to a Civil Rights Fight. Retrieved October 2012, from

AlterNet.org.

Ross, B. (2012, July 27th). PA Court Strikes Down

Limits on Municipal Zoning for Hydraulic Fracturing. Retrieved September

2012, from Knowledge Center.

Rothberg, P. (2010). The Perils of Hydro-Fracking.

Rubinkam, M. (2012, September). Pa. drilling impact

fees raises more than $200M. The Huffington Post/ Associated Press.

Seifried, R. (2013, March 8). Three New California

Bills Proposed to Further Regulate Fracking. Retrieved April 6, 2013, from

CliforniaEnvironmentalLawBlog.com:

http://www.californiaenvironmentallawblog.com/

Shearer, C. (2012, May). Fracking in California

Raises New and Old Concerns. Retrieved from Truthout.

Sheppard, R. (2012, July 26). Why Oil Companies

Want California’s Water. Retrieved April 8, 2013, from Roland

Sheppard.com:

http://rolandsheppard.com/Site/Why_Oil_Companies_Want_CA_Water.html

Song, L. (2013, March 31). Exxon Confirms

80,000-Gallon Spill Contains Canadian Tar Sands Oil. Retrieved April 5,

2013, from AlterNet.org:

http://www.alternet.org/environment/exxon-confirms-80000-gallon-spill-contains-canadian-tar-sands-oil

Suachy, D. R., & Newell, K. D. (2011). Hydraulic

Fracturing of Oil and Gas Wells in Kansus. Kansus Geological Survey.

The Wilderness Society. (2011, January). State

Hydraulic Fracturing Disclosure Requirement Fact Sheet.

USGS. (2010, November 3). FTP directory /maps/ at

hazards.cr.usgs.gov. Retrieved April 4, 2013, from

http://www.data.scec.org/ftp/maps/redlands/ (additional maps):

ftp://hazards.cr.usgs.gov/maps/qfault/

Wang, J., Ryan, D., & Anthony, E. J. (2011).

Reducing the greenhouse gas footprint of shale gas. Energy Policy (39),

8196-8199.

Wernau, J. (2013, March 21). Bill to regulate

fracking postponed. Retrieved April 5, 2013, from ChicagoTribune.com:

http://www.chicagotribune.com/business/breaking/chi-fracking-legislation-20130321,0,2964228.story

WHCU. (2012, September). Town of Caroline Passes

Fracking Ban. Retrieved November 2012, from WHCU870.com:

http://whcu870.com/Town-of-Caroline-Passes-Fracking-Ban/14214948

Wiseman, H. (2009). Untested Waters:The Rise of

Hydraulic Fracturing in Oil and Gas.

World Watch Institute. (2013, April 1). Jobs in

Renewable Energy Expanding. Retrieved April 1, 2013, from World Watch

Institute.org: http://www.worldwatch.org/node/5821

Hydraulic fracking should be banned because study say that this process contaminates the ground water and make it unfit for drinking .

ReplyDeleteHydraulic Installation Kits

Thanks

Bruce Hammerson

Yes that is absolutely correct. We don't really have a grasp on industry use of water in general let alone the oil and gas sector.

Delete